TV Adaptation of Classic Greek Novel Breaks Viewing Records in Greece

A highly anticipated international mini series co-production of Greek public broadcaster ERT is breaking viewing records in Greece.

A highly anticipated international mini series co-production of Greek public broadcaster ERT is breaking viewing records in Greece.

As Amadeus and Mozart/Mozart shine a fresh spotlight on the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, DQ speaks to the musicians behind the series to explore how they faced up to the challenge of meeting the legacy of the genius composer...

Beta Film has secured a wide-ranging multi-territory licensing agreement with CANAL+, bringing a premium selection of Beta’s high-end series to audiences across Europe...

Ahead of the highly anticipated premiere of Skam Croatia - Sram’s third season, the acclaimed Croatian adaptation of Skam is already celebrating fresh recognition on the international stage.

Expanding into Asia, Beta Film has acquired the worldwide distribution rights to its first Korean drama, the internationally acclaimed thriller series Snow White Must Die...

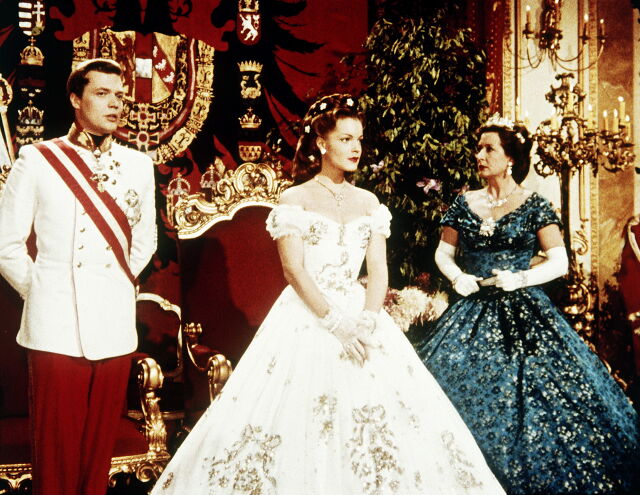

Romy Schneider is back: This holiday season, Beta’s classic movie trilogy Sissi will once again warm hearts all over Europe.

Crave's Suzane Landry and Trio Orange's Annie Sirois discuss how Empathie's success is opening doors for Quebec stories in the global market.

This series has shaped European high-end drama for nearly a decade: Germany’s landmark Babylon Berlin wrapped shooting for the fifth and final season in Berlin and goes straight into post-production...

The series has recently been honored with Austria’s prestigious ROMY Industry Award in the category Best Production, after Justus von Dohnányi won the German Bambi Award for Best Actor (national) for his role as the unscrupulous banker Bernd Hausner in the drama series...

Iconic German actor Udo Kier, known for his multiple collaborations with such stars as Madonna, Gus Van Sant, and Lars von Trier, has died in Palm Springs, California, at the age of 81.

Welcome to Global Breakouts, Deadline’s fortnightly strand in which we shine a spotlight on the TV shows and films killing it in their local territories. Breakout hits are emerging in pockets of the world all the time and it can be hard to keep track, so we’re doing the hard work for you...

There will be a change of leadership at Munich-based production and distribution group Beta Film: From April 2026 onwards, the current Chief Financial Officer Licensing & Distribution at Leonine Group, Stephan Katzmann, will take over the position of CFO.

New ways of thinking in the fields of artificial intelligence and virtual production: Beta Film and Filmakademie Baden-Württemberg (FABW) are establishing a strategic partnership.